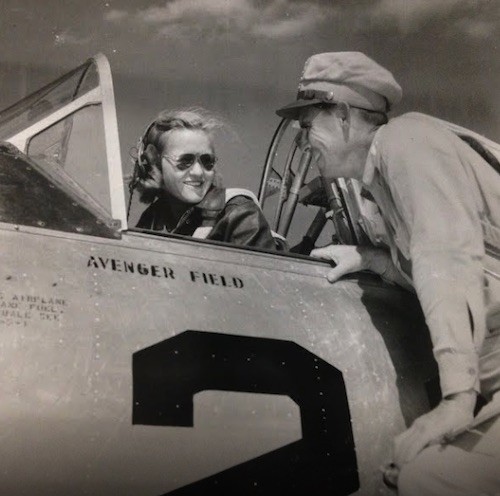

Joann Garrett was one of 1,074 women who served in the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs, during World War II. The WASPs completed a rigorous training program at Avenger Field in Texas, then served in non-combat military missions across the US during the war, such as ferrying planes from factories to bases and flight-testing aircraft. WASP Joann Garrett flew twin-engine B-26 planes and C-60 transport aircraft at Army Air Bases in Texas and Kansas in service to her country. Referring to themselves as “Avenger Girls,” the Women Airforce Service Pilots were superheroes of aviation. They were the first women to fly for the US military, paving the way for women to serve equally in the US Air Force. Women had been flying planes since the early 20th century, like Bessie Coleman, the first African American and Native American female pilot, and Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. As the US entered World War II in December 1941, the military needed more pilots for domestic duties, such as flight-testing and ferrying aircraft, in order to send male combat pilots overseas to fight in Allied efforts in the European and Pacific theatres. The US government had created the Civilian Pilots Training program at colleges and flight schools across the country in 1938, enabling young men and even a few women to gain flight time and experience. However, it wasn’t until two other pioneering female aviators formally pushed for official military-affiliated programs that more women began to train and serve as pilots in the war effort.

The Women Airforce Service Pilots program formed in 1943 by combining two separate but related civilian pilot programs for women within the Army Air Forces. In 1942, pilot Nancy Harkness Love started the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), in which a small number of female pilots transported military planes from factories to Army Air Bases. Pilot Jacqueline Cochran also gained military approval to start the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) to train classes of female pilots to serve in domestic non-combat missions. When these two groups merged to form the WASPs in the summer of 1943, Cochran led the program and Love served as the head of the ferrying division. Although the US military approved the Women Airforce Service Pilots program, the WASPs still officially held civilian status. The first woman to train as a pilot with the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, and graduate in the first class of WASPs, was Betty Gillies. She and Nancy Harkness Love later became the first women to pilot and ferry the Boeing B-17 bomber fortress. Gillies had over 1,000 hours of flying time by 1942, significantly more hours than what most male pilots had acquired. Women accepted into the WASP program all had flying experience and came from diverse backgrounds. WASP Adaline Blank (43-W-8), a former assistant buyer, wrote to her sister in her first month of the program, “There are salesgirls, college girls, teachers, stenographers. Every type and size but we all have this in common---- our hearts are in flying, so come what may, nothing else matters.”

WASP training was rigorous and very similar to male AAF cadet training. A typical training day at Avenger Field began at 6am and ended at 10pm. The WASPs cleaned their barracks for inspection, marched, then completed physical and drill training, flight instruction in link trainers, basic, or advanced aircraft, and studied weather, navigation, physics, math, and aircraft and engines, among other subjects. The WASP training program lasted about 27 weeks and at graduation, the pilots were well-equipped to fly all types of military aircraft. Eighteen classes of WASPs graduated during the war, a total of 1,074 women. At the graduation ceremonies at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, the WASPs earned their silver wings from program director Jacqueline Cochran. Although they did not serve in combat roles, the WASPs served in several crucial missions across the US during World War II. The missions were highly dangerous and required the utmost confidence and skill. Ferrying military planes was a primary duty of the Women Airforce Service pilots during the war. The pilots transported newly built planes from factories to military air bases all over the country to be used in training and combat. By the end of 1944, the WASPs had ferried more than 12,000 planes in the US, including basic trainer planes, fighter planes, and bombers. WASPs Barbara Erikson London and Evelyn Sharp ferried C-47s and P-51s, two types of aircraft used in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, a major turning point in the war for the Allies. Another important mission of the WASPs was serving on tow target squadrons. The pilots, including Laurine Nielson, Viola Thompson, Mary Clifford, and Lydia Linder, would fly planes with canvas targets attached to the back for male students to practice gunnery for combat, firing ammunition at the targets.

WASPs even instructed male pilots in ground school and flight training. Jane Shirley taught male officers at Foster Field in Victoria, Texas. Ethel Meyer Finley instructed male pilots in flying at Shaw Army Air Base in South Carolina, and she recalls that most male pilots and military officers on the bases had positive attitudes toward the WASPs and worked well together. She and other WASPs did experience gender discrimination, but the WASPs continued to complete their missions and serve their country despite these obstacles and hardship. WASP missions also included flight testing all types of military aircraft, such as four-engine bombers, an extremely important and dangerous task. In June 1944, the same month as the D-Day Invasion, WASPs Dora Dougherty and Dorothea Johnson Moorman flight tested the Boeing B-29 bomber Superfortress “Ladybird” for Colonel Paul Tibbets. Male Airforce pilots refused to flight test the bomber at an AAB at Clovis, New Mexico, thinking the mission too dangerous. Colonel Tibbets called for two WASP pilots to train on the B-29 then complete flight tests of the Superfortress “Ladybird.” Dougherty and Moorman successfully piloted the bomber, even while experiencing an engine fire during flight. Colonel Tibbets recalled that, “They did the job. And I don't know how we could have gotten people to fly B-29 airplanes without them.” He later served on the Manhattan Project and piloted the B-29 bomber Superfortress “Enola Gay” that dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945 at the end of World War II. Some WASPs did lose their lives in service to their country.

Cornelia Fort was the first WASP to die while on active duty in the US military. Before the WASP program started, Fort witnessed from the air the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, while she was conducting civilian flight instruction. She joined the WAFS as the second female pilot and was later assigned to ferrying missions. Cornelia Fort died on March 21, 1943 in an aircraft collision at only 24 years old.

WASP Hazel Ying Lee, the first Chinese-American woman to fly in the US military, served at Romulus AAB in Michigan, then trained in Pursuit School in Texas. She was also among the first women to fly fighter planes in the US military, such as P-63 Kingcobras. While on a ferrying mission to provide planes like the P-63 Kingcobra to allies under the Lend-Lease program, Lee became the first Chinese-American woman to die in service to the United States. While landing the plane at a base in November 1944, another plane collided with hers and crashed.

WASP Hazel Ying Lee, the first Chinese-American woman to fly in the US military, served at Romulus AAB in Michigan, then trained in Pursuit School in Texas. She was also among the first women to fly fighter planes in the US military, such as P-63 Kingcobras. While on a ferrying mission to provide planes like the P-63 Kingcobra to allies under the Lend-Lease program, Lee became the first Chinese-American woman to die in service to the United States. While landing the plane at a base in November 1944, another plane collided with hers and crashed.

Because the WASPs were not militarised, the US military did not provide transport home for the deceased pilots and did not pay for their funerals. The WASPs worked together to provide funds for the 38 women who died while serving as Air Force service pilots during World War II. The WASP program disbanded in December 1944, eight months before the end of World War II. It was the only branch of women’s service in WWII to not receive military status during the war and the only branch to be disbanded before the war ended. Jacqueline Cochran had pushed for militarisation in Congress during the war, but despite support the bill was ultimately defeated. According to historians, one of the major reasons for deactivation of the WASP program was opposition from a group of male pilots who were concerned that female pilots would take their jobs after returning from combat duty. After World War II ended, limited options existed for the WASPs. In 1948, women could transfer to Women in the Air Force, or WAF, although they could not pilot aircraft. Ola Mildred Rexroat, the only Native American woman to serve in the WASPs, transferred to the WAF and served as an air traffic controller. Other WASPs worked in aviation by becoming commercial pilots, flight instructors, and stewardesses. Some women also continued to fly planes in their free time. Many women of the WASP program quit flying altogether, choosing other lines of professional and domestic work. The WASPs continued to advocate for official military status. In the 1970s, they pushed legislation into Congress, calling for the full militarisation of the Women Airforce Service Pilots. On November 23, 1977, more than 30 years after the WASP program started, President Jimmy Carter signed Public Law 95-202 giving the women who served as civilian Airforce pilots during WWII veteran status. In 2009, President Barack Obama signed a bill to award the WASPs Congressional Gold Medals, one of the highest civilian honors awarded by the United States Congress.

You can find our recreation of the classic WASP B-17 jacket here