The United States Coast Guard is the United States oldest and premier maritime agency. The history of the Service is very complicated because it is the amalgamation of five Federal agencies. These agencies, the Revenue Cutter Service, the Lighthouse Service, the Steamboat Inspection Service, the Bureau of Navigation, and the Lifesaving Service, were originally independent, but had overlapping authorities and were shuffled around the government. They sometimes received new names, and they were all finally united under the umbrella of the Coast Guard. The multiple missions and responsibilities of the modern Service are directly tied to this diverse heritage and the magnificent achievements of all of these agencies.

The Coast Guard, through its forefathers, is the oldest continuous seagoing service and has fought in almost every war since the Constitution became the law of the land in 1789. Following the War of Independence (1776-83), the Continental Navy was disbanded and from 1790 until 1794, when Congress authorised the construction of six frigates (of which only three were launched by 1797), the revenue cutters were the only national maritime service. The Acts establishing the Navy also empowered the President to use the revenue cutters to supplement the fleet when needed. Laws later clarified the relationship between the Coast Guard and the Navy.The Coast Guard has traditionally performed two roles in wartime. The first has been to augment the Navy with men and cutters. The second has been to undertake special missions, for which peacetime experiences have prepared the Service with unique skills.

Following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the Coast Guard carried out neutrality patrols as set out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 5 September 1939. The Coast Guard's fleet of cutters and craft first began sailing into harm's way on the Atlantic after the establishment of the Neutrality Patrol in 1939 and then into real danger escorting convoys in 1941, all prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Direct action with the German Navy soon followed. The USS Alexander Hamilton, CG fell victim to a U-boat's torpedo in January, 1942, becoming the first US warship lost in combat in the Atlantic after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Cutters countered and quickly drew blood, sinking three U-boats off the East Coast in 1942. Coast Guardsmen on board the cutter Icarus, which sank U-352, gained the distinction of being the first U.S. servicemen to take German prisoners of war.

The cutters themselves, most of which had been constructed between the wars, were designed to have additional armament added in case of national emergency. The Navy added this additional armament beginning in 1940, including more and heavier guns, depth charge tracks, "Y" and "K" guns, additional anti-aircraft weaponry, and sonar equipment. After the start of the war, cutters were some of the first Allied vessels fitted with newly developed electronic gear, such as high-frequency radio direction finders, known as HF/DF or "huff-duff," and surface and air search radars.

On April 9, 1941, Greenland was incorporated into a hemispheric defence system. The Coast Guard was the primary military service responsible for these cold-weather operations, which continued throughout the war. On September 12 the cutter Northland took into "protective custody" the Norwegian trawler Buskoe and captured three German radiomen ashore. This was the United States' first naval capture of World War II. Although most of the 327s were initially assigned to duty in Greenland, but their exposed propellers were easily damaged by ice. Consequently they were assigned as convoy escorts on the North Atlantic. Later, they escorted convoys across the mid-Atlantic, past Gibraltar, and through the Mediterranean to North Africa. After their distinguished service in the Battle of the Atlantic, the surviving 327s were converted to amphibious force flagships and served during some of the most intense battles of the Pacific Theatre.

If any battle marked the turning point of World War II in the Pacific, most experts agree that the six-month land, sea and air battle for Guadalcanal was the one. American naval strategists drew a line in the sand at Guadalcanal because enemy aircraft flying from that island could cut-off Allied supply lines to Australia.

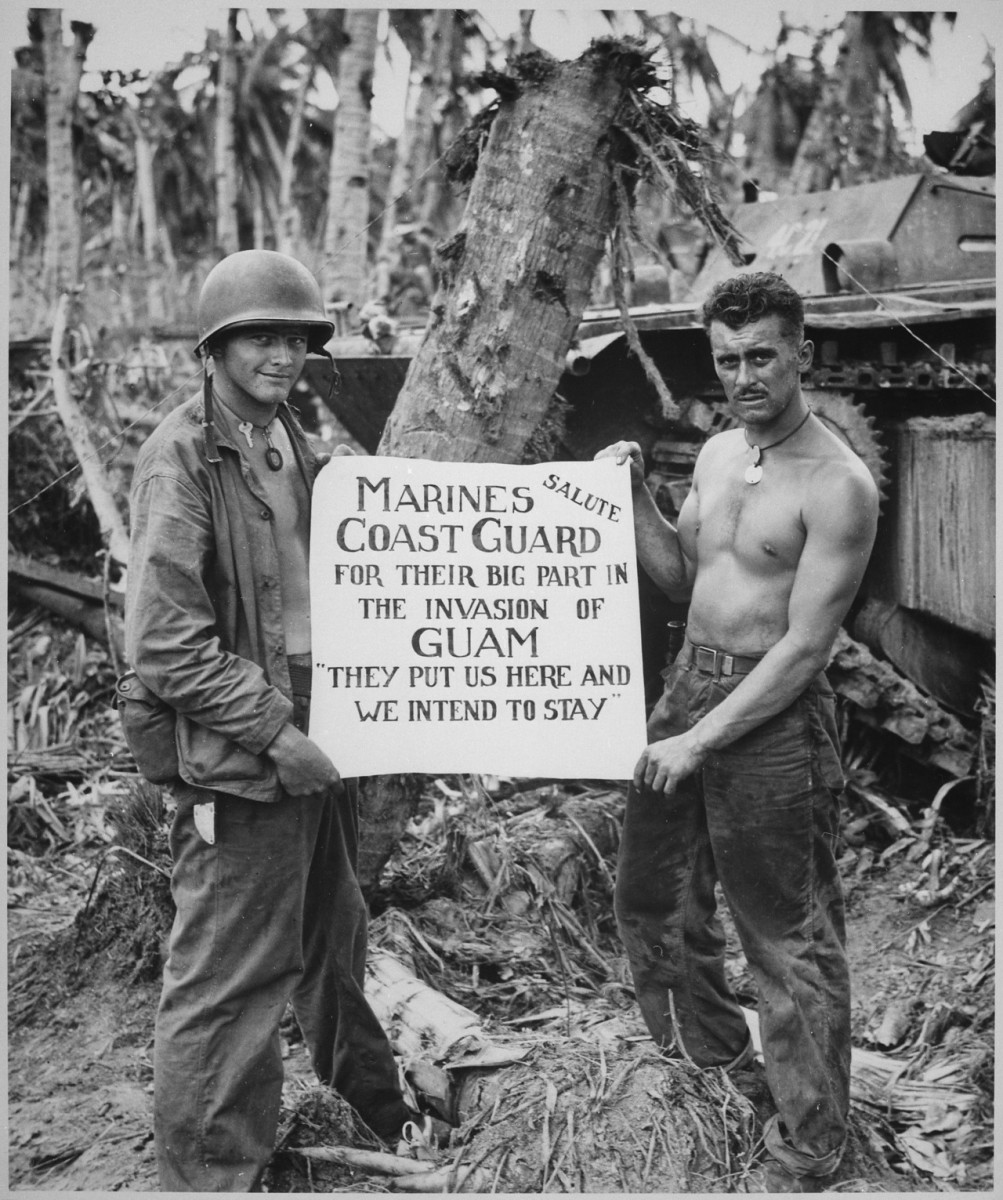

During the Guadalcanal offensive, the U.S. Coast Guard served an important role through its specialties in maritime transport, amphibious landing and small boat operations. On ‘the Canal,’ the Coast Guard worked seamlessly with its USN and USMC counterparts and, for the first time in its history, commanded and manned a U.S. Naval Operating Base, or NOB. Coast Guard Lt. Cmdr. Dwight Hodge Dexter commanded NOB “Cactus,” the code name for Guadalcanal’s naval base. At its peak, NOB Cactus included about thirty LCPs, also known as Higgins Boats, and a dozen bow-ramped tank lighters. About 50 officers and enlisted men manned the operation, which included an odd collection of coconut plantation buildings, homemade shacks and tents; and log-reinforced dugout shelters for surviving air raids, naval bombardment and artillery shelling.

On the morning of Aug. 7, 1942, exactly eight months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the first American amphibious operation of World War II was about to begin. The cloud cover of the previous days and circuitous voyage from Wellington, New Zealand, had hidden the invasion fleet’s movements from enemy aircraft and submarines, so Japanese forces on Guadalcanal received no forewarning of an impending attack. The fleet entered Sealark Channel near the landing beaches and front line warships began shore bombardment of enemy positions on the island. The waves of Marines coming ashore greatly outnumbered the combined strength of Japanese military forces and civilian construction personnel responsible for building the enemy’s new airfield. The Japanese beat a hasty retreat from their shore positions into the jungles of Guadalcanal. Within a day of the landings, the Americans had captured the partially completed airstrip and established a defensive perimeter around the airbase.

Dexter was a natural leader who was devoted to his crew. When the enlisted men on board troop transport Hunter Liggett heard that he would command Guadalcanal’s small boat operations, several volunteered to serve with him. On Aug. 8, 1942, Dexter came ashore with the first 24 Coast Guardsmen to serve at NOB Cactus. He set up his headquarters in the former manager’s house for the Lever Brothers coconut plantation, which was located within the Marine’s defensive perimeter at Kukum, east of Lunga Point. The white frame structure was in good condition considering the naval bombardment that had softened up the beaches the day before. Near Dexter’s headquarters, his men built a small tool shed for servicing their landing craft and machinery. They also built a signal tower out of coconut logs and a makeshift shelter located underneath it built of packing crates with a tent roof. This shelter housed Coast Guard heroes, including signalman Douglas Munro, later recipient of the Service’s only Congressional Medal of Honor, and Ray Evans, later recipient of the Navy Cross. The rest of Dexter’s men had similar shelters or tents, but all lived close to the log-reinforced bomb shelters.

NOB Cactus held a variety of titles. In the Presidential Unit Citation awarded to the First Marine Division, Reinforced, the added word “Reinforced” refers to the Coast Guard unit. NOB Cactus also formed part of Transport Division 7 and it had the moniker of “Local Defense Force and Anti-Submarine Patrol, Guadalcanal-Gavutu.” These names indicate the variety of missions carried out by Dexter’s unit. NOB Cactus served primarily to run supplies and troops from transport ships to the beaches of Guadalcanal, but Dexter’s men and landing craft performed far more missions than merely supplying the troops. They provided an important radio and communications link between land forces and offshore vessels. They navigated the waters of Guadalcanal and islands as far distant as 60 miles to land Marines and retrieve them when necessary. They inserted reconnaissance teams led by British Colonial Forces officers behind enemy lines. In the aftermath of aerial dogfights above and naval battles on the surface of nearby Iron Bottom Sound, NOB watercraft took to open water to retrieve wounded Americans and Japanese prisoners. For a time, NOB personnel fitted their landing craft with depth charges and conducted nightly anti-submarine patrols. Coast Guard personnel also pitched-in to defend American positions by serving artillery pieces and providing infantry support. The men even trawled off the beaches, catching fresh fish to supplement the meagre menu of Marines at the local mess hall.

The men of NOB Cactus used the dugout bomb shelters frequently due to aerial bombing, naval shelling and artillery bombardment that took place on a regular basis. Under cover of darkness, Japanese naval units from their base at Rabaul, New Britain, regularly attacked Guadalcanal and its defending Allied warships. The men on the Canal also suffered through daily air attacks, which tore up the airfield and prevented transports from lingering off the beaches for any length of time. In fact, Dexter maintained a captured Japanese three-barrelled machine gun, referred to by a British observer as a “Chicago piano,” to defend against air attacks. During the initial stages of the campaign, enemy artillery and sniper fire also hounded the men at NOB Cactus. The Japanese had salvaged a deck gun from one of their grounded ships and mounted it in the jungle highlands commanding the airfield. Nicknamed “Pistol Pete” by the Americans, the Japanese used this gun to lob several rounds per day at American positions until an American air attack finally silenced the gun. After dark, the Japanese also sent aircraft over Guadalcanal to bomb the Marines and prevent them from enjoying more than a few hours of uninterrupted sleep. Due to the constant shelling and bombing, the NOB Cactus crew aptly named their nearby lagoon, “Sleepless Lagoon.”

Dexter’s men and landing craft kept critically needed supplies flowing to the First Marine Division on Guadalcanal. During his command of NOB Cactus, Dexter made sure his men had plenty of food and supplies and trained them in air raid drills, digging foxholes and the use of slit trenches for cover. One of the men later wrote about Dexter, “I felt I could stand the bombings, shellings and artillery so long as he was there. He gave us the feeling of safety that only good officers can give to their men.”

In the condolence letter to Coast Guard Medal of Honor recipient Douglas Munro’s parents, Dexter referred to Munro as “one of my boys.”

Like many who served in the early part of the Guadalcanal campaign, Dexter contracted malaria. In November 1942, when the disease finally got the best of him, Dexter rotated back to the United States. He had earned the respect and admiration of those who served under him at NOB Cactus. Some of his men broke down and cried when he finally announced he was redeploying for home. The Navy awarded Dexter the Silver Star Medal for his command of NOB Cactus.

His medal citation aptly concludes, “By his courage in the face of great hardship and danger, he set an example which was an inspiration to all who served with him.”

When Dexter departed Guadalcanal, the battle had entered its fourth month, but by then the Americans had become experienced jungle fighters and secured their position on the island. The defeat of Japanese forces on the Canal appeared assured by late 1942 as elements of the U.S. Army relieved the malaria-ridden First Marine Division. In early 1943, commander of U.S. forces on Guadalcanal, US Army General Alexander Patch declared the island secured of all Japanese military forces.

Guadalcanal was a killing field that consumed thousands of men, hundreds of aircraft and dozens of front line warships. Even though the U.S. Navy had triumphed earlier in 1942 at the pivotal naval battle at Midway, the struggle for Guadalcanal proved the first true test of all branches of the American military against determined enemy forces within Japanese-held territory. After Guadalcanal, the Allies would remain on the offensive for the rest of the war and the Japanese would fight a lengthy retreat all the way back to their home islands.

Dexter returned to the States having lived through a lifetime’s worth of vivid and often horrific experiences. For the remainder of the war, he rose through the officer ranks at bases within the United States. His post-war assignments included a tour in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where he had lived as a child. He also served as commander of the high-endurance cutter Dexter, which is unrelated to his family. In September 1959, he retired from the Service as a rear admiral, after a 35-year career. Dexter was a member of the long blue line and served in the Coast Guard with distinction both in combat and in peacetime.